The Futuro Is Bleak: The Disillusionment of Matti Suuronen’s UFO Home

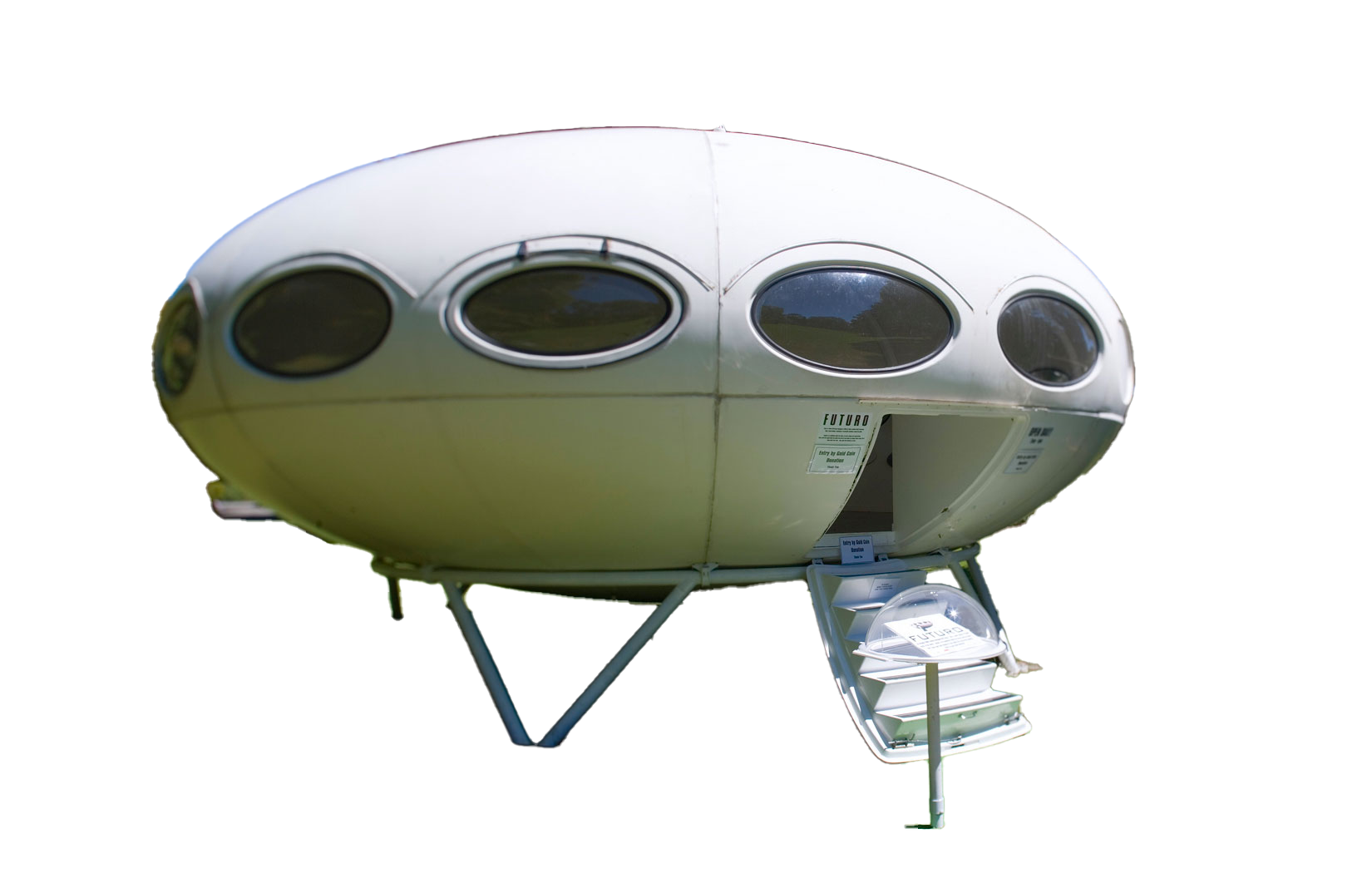

Perhaps Matti Suuronen’s Futuro miscalculated when to land on the snowy Finnish1 countryside. Scrutinized by fellow Finnish architect Reijo Jallinoja as a home that “satisf[ied] the eccentric quirks of a small handful of buyers,” the unfortunate July 20th 1969 touchdown of the2 first Futuro was out shined that day by Apollo 11’s Moon landing, foreshadowing its failed destiny. Disappointment characterized the Futuro both in the late sixties and retrospective writing, deemed “too quirky, too expensive for the mass market,” their mass graves litter the3 American landscape either in states of disrepair, or repurposed as fantasies of the space age fulfilling its plastic promise. The science fiction of the Futuro had blurred the lines of reality for consumers, leaving most with no choice but not engaging with this foreign architectural visitor. This same public, however, was enraptured with the future for decades: ultramodern visions of new (and improved!) lives existed in the streamlined products and pavilions of Norman Bel Geddes, or the pulp fiction of Amazing Stories, with covers by Frank R. Paul. Just what was it that made Futuro’s so repulsive, so unappealing? Existence. The physical production of Futuro’s was too much for consumers willing to embrace the space age in bursts of small objects and print culture, but not ready to live in a plastic UFO. To investigate the fall of the Futuro, it must be dissected into two: the image and the material product. The Futuro’s lack of success can be discovered in the incoherence between its image and its reality, never fulfilling any expectation of either.

Image 1 - J.P. Karna, A Futuro at Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Finland, 2013, digital photograph, 1,022 × 681 pixels, Tapiola, Finland https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Futuro_WeeGee_Espoo.jpg

Image 2 - Archigram, Archigram 4: Zoom. Magazine. Architecture without Architecture. http:// architecturewithoutarchitecture.blogspot.com/2012/12/the-amazing-archigram-4-zoom issue-1964.html

The Futuro’s first mistake was the fact they were photographed. Photography deepened the reality of the upcoming future, in comparison to Suuronen’s contemporaries who left their visions of the future to illustration. Plug-in-City by Peter Cook appeared in Archigram 4 as part of a comic book series, leaving no question of the quick, consumable nature of the space age future as an image. Far less avant-garde, futurist Arthur Radebaugh’s series Closer Than We 5 Think showcased the fictional possibilities of scientific advancements trickling into our lives.6 7 Photography of The Futuro was the chief propagandist in what Susan Sontag referred to as the desire “to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs,” an “aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted,” where in photographs of Futuro’s were8

Image 3 - Radebaugh, Arthur. Closer Than We Think!: A-Frame River Villa. 1960. Comic Strip. We Are Moving Stories http://www.wearemovingstories.com/we-are-moving-stories-videos/ 2017/12/12/other-worlds-austin-sci-fi-film-festival-closer-than-we-think

hoping to succeed in bringing to life that which was sold as illustration before. In the first brochure for Futuro’s produced by Polykem in 1969, a family is shown playing a board game9 and tucking their children to sleep, echoing the family oriented visions of Suuronen. This approach was not deemed successful enough in selling the image of the UFO home. Photography then helped regulate Futuro’s to spaces of momentary leisure: the lucrative vacation home. The January 1970 issue of Science & Mechanics advertises Futuro’s as a vacation home that can be10 readily “plugged in” anywhere it goes. Two months later in the March 1970 issue of Popular Science , Futuro’s are vacation homes, photographed alongside other pre-fabricated homes, the11 other homes less jarring on the landscape. This ideal of the Futuro as a family friendly home, be it permanent or vacation does not last for editorial teams. Photographs of Futuro’s as vacation homes helped transition the Futuro to a more acceptable idea: a bachelor pad. Subsequent brochures by Polykem later show the Futuro as a place for bachelor’s and their many friends, a stage set to become voyeur of a young woman . The Futuro’s inclusion in Playboy’s September12 1970 issue as a “portable playhouse,” or in a sadomasochistic porn spread in Swedish magazine Private in 1971 where women are tied to the built-in furniture and beaten exemplified the13 misogyny infused cocktail ideal that transformed the Futuro from the sphere of the domestic to the sphere of the single male not looking to be tied down, but who ironically couldn’t afford Futuro’s.

Image 4 - Polykem. Brochure for Futuro. 1969. The Futuro House.

http://www.thefuturohouse.com/Futuro House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection-Magazines.html

Image 5 - Science & Mechanics, January 1970. Magazine. The Futuro House. http:// www.thefuturohouse.com/Futuro-House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection Magazines.html

Image 6 - Popular Science, March 1970. Magazine. The Futuro House. http://www.thefuturohouse.com/ Futuro-House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection-Magazines.html

http://www.thefuturohouse.com/Futuro House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection-Magazines.html

Image 5 - Science & Mechanics, January 1970. Magazine. The Futuro House. http:// www.thefuturohouse.com/Futuro-House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection Magazines.html

Image 6 - Popular Science, March 1970. Magazine. The Futuro House. http://www.thefuturohouse.com/ Futuro-House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection-Magazines.html

It’s that state of sexual fantasy that helps sell the Futuro across America, but no longer as a prefabricated home, but as a commercial space. The Futuro, instead, is an image of science fiction fantasy, a sideshow freak that fits well along roadside novelty architecture. Of the only 100 that were ever produced, Futuro’s surrendered their purpose, many becoming advertisers for local businesses. One famous example, at Monty’s Pier in Wildwood, New Jersey, saw a Futuro re-themed to various sci-fi films over the years, such as Star Trek, Planet of the Apes, and the first two Star Wars. Today, this same Futuro exists as a rotting husk in the back of The Bait Box14 Restaurant in Greenwich, New Jersey. Affectionally called “Dusty” by its owner, the decrepit15 astro zombie is a perfect analogy of how Futuro’s could not thrive beyond photography, especially those of the original Polykem brochures. The image of the Futuro in print culture is the only proof of a human race who would have considered living in a UFO house. This pathetic present for The Futuro brings us closer to reality, to the reality of the product. The Futuro was meant to exist alongside a present that wasn’t truly so space age. “Houses of the Future” were part of theme parks and museums, but hadn’t been brought to either the suburb or the city quite yet. The disappointment of the final product was experienced by those “fortunate” enough to buy one in its technological quirks and paradoxic immovability, which subjected Futuro’s across the world to alterations that took away its “space age”-ness. In other words, the incoherence between the shiny image of The Futuro and the actual product exists because they weren’t good homes in their original state.

Image 7 - Futuro Ride at Morey’s Pier, 1974. Film Photography. Funchase. http://www.funchase.com/ Images/Moreys/Moreys.html

Futuro’s were certainly part of the same space age which ushered (currently) unusable designs like those of Archigram, because its technology was profoundly inconvenient for the average person to tackle. Its materiality was both its allure and most powerful adversary. Suuronen labored over the design, fighting for the use of new materials in the Futuro’s final form. Original patents called for an acrylic dome with concrete pillars , but this only16 strengthened the powers of the Sun which caused it to overheat, the celestial body the Futuro was sworn to protect against. Significant changes had to be made to promise the public a plastic home. Made of polyurethane in its final form, it took only 30 minutes to heat up in even the harshest of winters. The price, however, was the wastefulness of its heating process, which required the user to step outside while it was cold and pour fossil fuels and crude oils into a hole at the bottom of their Futuro to burn and create heat. The Oil Crisis of 1973, which tripled the price of plastics, lead to a double whammy for Futuro’s: you can’t heat the existing ones, and you can’t make new ones. The fate of its material made the Futuro extremely expensive, evidence for its shift of being advertised as a vacation home for the wealthy, as opposed to utopic living space for the family. There also exists what plastic meant to a public, at least an American one, who in the year of the Futuro’s emergence (1968) had to face the challenges at home and abroad regarding the Vietnam War and the Civil Right’s Movement. A year that seemed to destroy the optimism of the majority of the decade, plastics were losing their status of being en vogue. A future where everything was possible through plastics wasn’t so likely in the threat of larger global issues, the same global population which came together at the rush of competing to see who would take ownership of the skies and stars above.

Global populations bonded over how to make the Futuro actually livable. American’s were presented with a home that contradicted their search for privacy for a nuclear family in the post-war period due to its shared domestic space. Matti Suuronen’s own Finnish values is the culprit of this American dilemma, having designed for the Scandinavian family that adored “wall-free togetherness” over enclosure. American companies with the license to construct Futuro’s came up with a solution which greatly decreased the area of the cramped spaceship: a 500 square foot wall, making tiny bedrooms that mimicked space capsules that, unlike the17 situation of astronauts revolving around Earth, was not a temporary pad. New Zealander’s, approached the dilemma of the plastic coldness of their flightless home with a D.I.Y. mindset, adding heavily patterned wallpapers, shag carpets, purple vinyl seating, and curtains. New Zealanders additions to their Futuro’s showed how ill-prepared upon arrival was The Futuro in creating a home. Prototype’s of the Futuro had demonstrated a beautiful color palette, almost18 like Verner Panton’s interiors, but the final product that was deliverable via helicopter (and usually through truck) had an interior that disappointed . Drab and immovable, Futuro’s19 interiors contends as the space age’s most boring interior. Paradoxically, Futuro’s were not exemplifying the traits of the space age that were popular with consumers, such as portable furniture and accesories. Eero Aarnio’s Ball Chair, to keep our discussion Finnish, could not fit within a Futuro, competing for space alongside the built in chairs/sofa beds that were not20 curvilinear or privately sensuous like the Ball Chair, but a tragedy of jaggedness that felt like

Image 8 - Teddy Quidit, Futuro Home Kitchen, 2011, digital photograph, 1500 x 1125 pixels, Rotherdam, Netherlands. https://www.flickr.com/photos/teddy_qui_dit/6185946195/

Image 9 - Futuro Kitchen, 2014. Digital Photograph. The Pod Up North. http://www.thefuturohouse.com/ Futuro-Wisconsin-USA-PodUpNorth.html

Image 10 - Futuro Chair/Bed Unit, Lot #38, Quittenbaum Auction 115A “Scandinavian Design”, Quittenbaum Auction Catalog. The Futuro House. http://www.thefuturohouse.com/ Futuro-House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection-Collectibles.html#quitten

Image 9 - Futuro Kitchen, 2014. Digital Photograph. The Pod Up North. http://www.thefuturohouse.com/ Futuro-Wisconsin-USA-PodUpNorth.html

Image 10 - Futuro Chair/Bed Unit, Lot #38, Quittenbaum Auction 115A “Scandinavian Design”, Quittenbaum Auction Catalog. The Futuro House. http://www.thefuturohouse.com/ Futuro-House-Books-Magazines-Memorabilia-My-Collection-Collectibles.html#quitten

a rushed solution for the Futuro, or maybe mathematic, as Suuronen would put it. A pre-fab house which required the owner to make livable through too many investments was not only a nuisance, but went against the space age ethos. Where was the convenience and speediness of the future that had arrived? Inspired by technology and the rationality of science, the Futuro should have been perfect from the beginning. It wasn’t, but that’s where their cadaver provides new ideas for the design historian.

Design historians tend to focus on objects are typical of an era, as typical of an era and mindset we cannot travel to the past and experience, subjugating an object’s placement due to its similarity to a canon of motifs and ornaments. Studying that special merging between the image and object recognizes that objects outgrow a box marked “space age”. Of course, this suggests no design movement is neat, which problematizes the whole field, which both inconveniences and excites the field. Peter Hall suggests that the object becomes a thing when it has failed, and21 that the object’s failure to function strips it of being worth consideration. The function of failure and disregard, despite an object fitting a “look” so well, is not a path many take. Maybe that’s why Futuro’s were not salvaged by design museum’s, and are now “things” in backyards, rusting away. That too, is fine. Let’s cut Futuro’s some slack: much can be learned about people who time travelled to the past when confronted with the future. I elect for Futuro’s to be seen in major design museums across Earth, but not in the form of its image, for that rusty shell, weakening legs, and degrading plastic are its final destination. It is imperative that design historians and theorists study how objects have turned out at the end of their lives. The shock of spotting the rare disintegrating Futuro in the wild, and learning of that architectural alien’s defeat on Earth, says more than how space age it appears.

Citations:

1See Image 1.

2Reijo Jallinoja, “The Future-Much Ado About Nothing,” Helsingin Sanomat, August 1969.

3Marko Home and Mika Tanila, Futuro: Tomorrow’s House From Yesterday (Helsinki: Desura, 2003), 32.

4Home and Tanila, Futuro, 92.

5See Image 2.

6See Image 3.

7Norma Brosterman, Out of Time: Designs for the Twentieth Century (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 95.

8Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Rosetta, 2005), 19, Kindle.

9See Image 4.

10See Image 5.

11See Image 6.

12Home and Tanila, Futuro, 151

13Home and Tanila, Futuro, 160

14See Image 7.

15“Greenwich, New Jersey: Flying Saucer-Futuro House,” Roadside America, Accessed October 30th, 2018, https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/8513.

16 Home and Tanila, Futuro, 13.

17Home and Tanila, Futuro, 114.

18See Image 8.

19See Image 9.

20See Image 10.

21Peter Hall, “When Objects Fail: Unconcealing Things in Design Writing and Criticism,” Design and Culture 6, no. 2 (2014): 162.

Bibliography:

Brosterman, Norman. Out of Time: Designs for the Twentieth Century. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Hall, Peter. “When Objects Fail: Unconcealing Things in Design Writing and Criticism.” Design and Culture 6, no. 2 (2014): 153-168.

Home, Marko and Mika Taanila. Futuro: Tomorrow’s House From Yesterday. Helsinki: Desura, 2003.

Jallinjoja Reijo, “The Future-Much Ado About Nothing.” Helsingin Sanomat, August 1969.

Roadside America. ““Greenwich, New Jersey: Flying Saucer-Futuro House,” Accessed October 30th, 2018. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/8513.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Rosetta, 2005. Kindle.

2Reijo Jallinoja, “The Future-Much Ado About Nothing,” Helsingin Sanomat, August 1969.

3Marko Home and Mika Tanila, Futuro: Tomorrow’s House From Yesterday (Helsinki: Desura, 2003), 32.

4Home and Tanila, Futuro, 92.

5See Image 2.

6See Image 3.

7Norma Brosterman, Out of Time: Designs for the Twentieth Century (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 95.

8Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Rosetta, 2005), 19, Kindle.

9See Image 4.

10See Image 5.

11See Image 6.

12Home and Tanila, Futuro, 151

13Home and Tanila, Futuro, 160

14See Image 7.

15“Greenwich, New Jersey: Flying Saucer-Futuro House,” Roadside America, Accessed October 30th, 2018, https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/8513.

16 Home and Tanila, Futuro, 13.

17Home and Tanila, Futuro, 114.

18See Image 8.

19See Image 9.

20See Image 10.

21Peter Hall, “When Objects Fail: Unconcealing Things in Design Writing and Criticism,” Design and Culture 6, no. 2 (2014): 162.

Bibliography:

Brosterman, Norman. Out of Time: Designs for the Twentieth Century. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Hall, Peter. “When Objects Fail: Unconcealing Things in Design Writing and Criticism.” Design and Culture 6, no. 2 (2014): 153-168.

Home, Marko and Mika Taanila. Futuro: Tomorrow’s House From Yesterday. Helsinki: Desura, 2003.

Jallinjoja Reijo, “The Future-Much Ado About Nothing.” Helsingin Sanomat, August 1969.

Roadside America. ““Greenwich, New Jersey: Flying Saucer-Futuro House,” Accessed October 30th, 2018. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/8513.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Rosetta, 2005. Kindle.